By Alexandra D’Arcy and Derek Denis

This paper is a little different. Instead of designing a study and coming up with a bunch of stats, D’Arcy and Denis got to thinking about the term “Postcolonial English” and its use. Their conclusion might surprise you!

This paper is great for woke bishes, epistemological hunnies, nomenclature nerds, and Indigenous scholars.

Under Investigation

the term “Postcolonial” and the study of Colonial Englishes

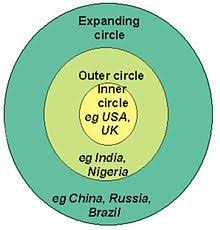

The term “Postcolonial Englishes” comes from Schneider (2007). He used it to describe any English that developed under any colonial system. Even though Postcolonial Englishes (PCEs) are all different from each other, Schneider thought that there might be a way to write a unifying theory about them since they all developed under the colonizers.

The Evidence

Englishes spoken in Canada, Australia, Singapore, and India

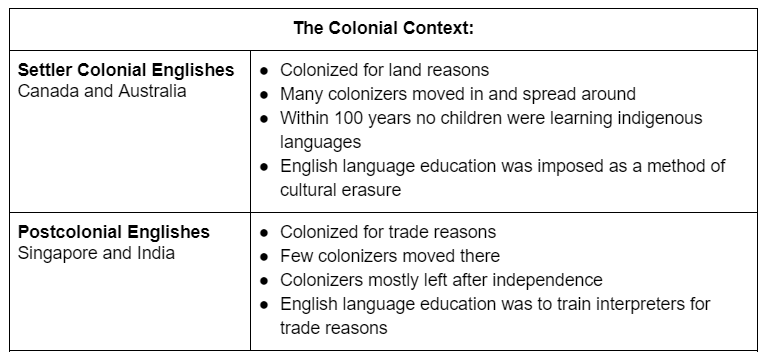

Singapore and India are no longer under English colonialism and their Englishes developed independently of English imperialism. Canada and Australia, on the other hand, are still under their settler colonial overlords. So perhaps Singapore and India could be considered PCEs, but not Canada and Australia.

So instead of the unifying theory that Schneider proposed, our authors are thinking, wait, maybe World Englishes aren’t a monolith?

The Proposal

a new perspective

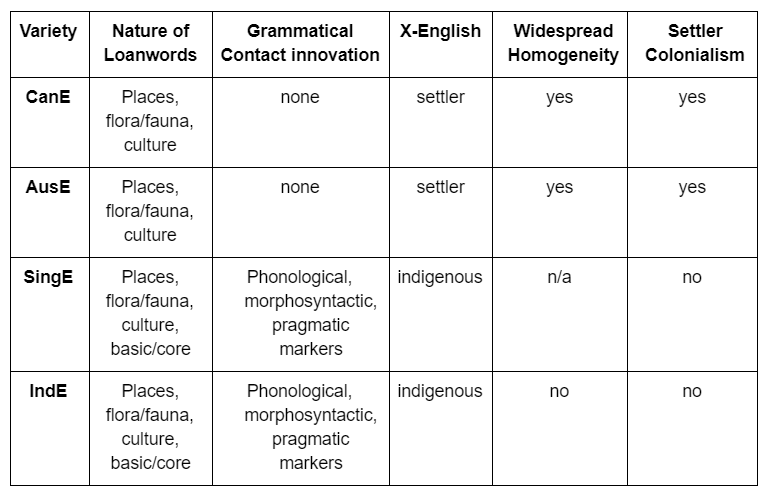

Basically, calling English post-colonial is nonsensical when the settlers are still all there. We can’t use it in Canada, the US, New Zealand, or Australia for sure. Present colonialism in these areas is called “Settler Colonialism” because there’s nothing “post” about it. Therefore, we should call the various Englishes that emerged in these places “Settler Colonial Englishes” (SCEs).

Now before you think this is just a semantics game, listen up. There are sociolinguistics implications of making this change in terminology.

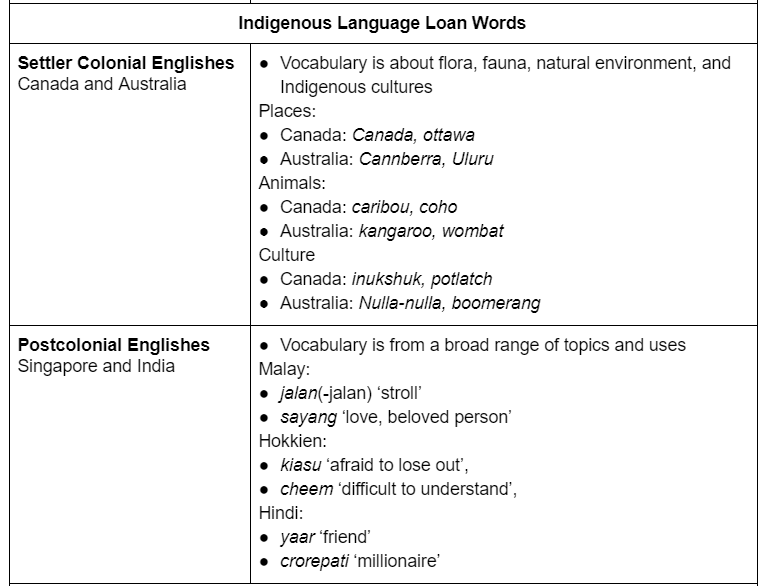

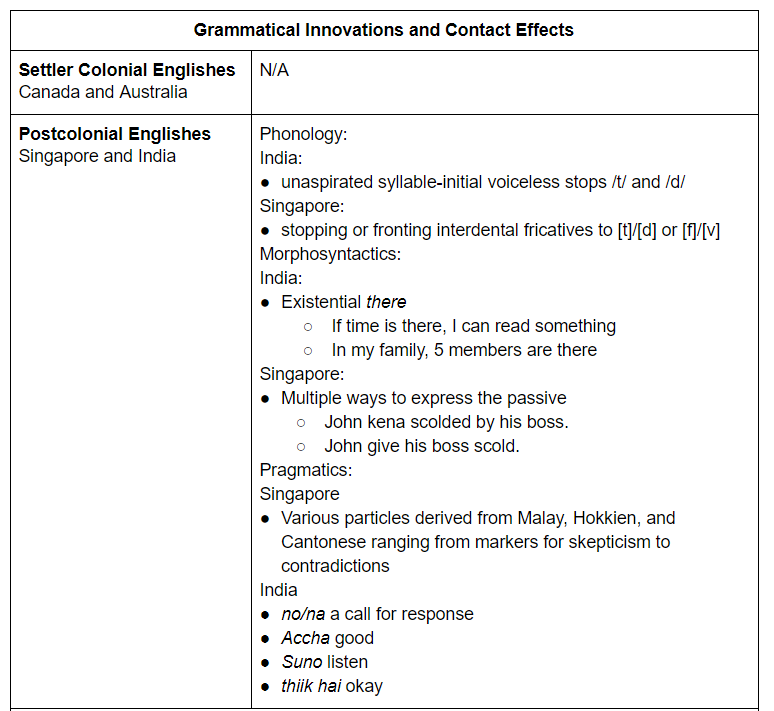

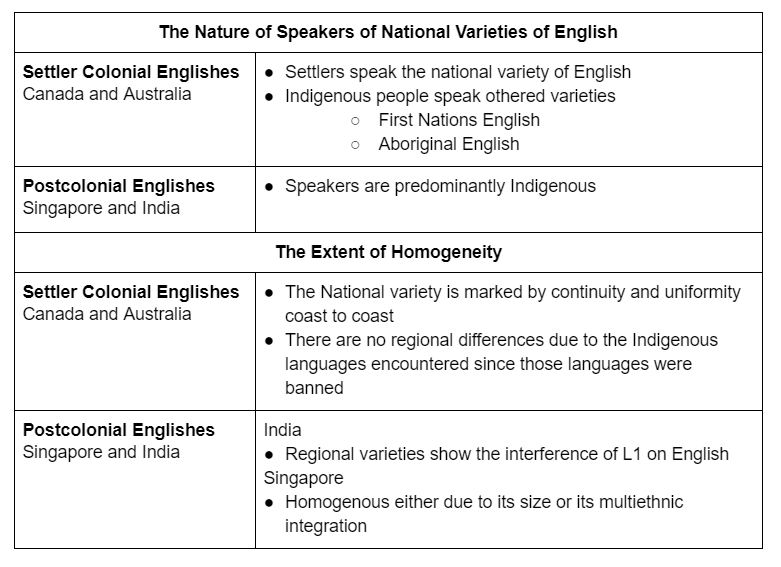

Not every colony was colonized by its colonizers in the same way. For example, did you know that there are actually places where colonizers just wanted resources or trade, and the indigenous people weren’t systematically erased? India and Singapore are examples of this. In those places, the indigenous languages have a lot more influence on the varieties of English that developed.

Where the colonists designed policies to eradicate people, their culture, and their language, there is almost no influence of indigenous languages on their variety of English. This is because language is inseparable from culture. When the culture is imperialism, the languages reflect that.

Settler Colonialism (and the “Natural” Emergence of English Varieties)

Case study: Canada

The vast majority of indigenous languages in Canada are severely endangered because of colonial policies that prohibited their use.

“Settler Colonialism operationalizes domination as a structure, not an event necessitating the cultural, political, social, and linguistic disappearance of the Indigenous population(s).”

(Wolfe 2006, 388)

Colonizers came to Canada with the intention of gaining land. They weren’t looking for people to integrate into their society or for laborers. They imposed notions of “status” and a pass system to control where indigenous people could go. They also used physical violence, family separation, outright baby stealing (it was called the child welfare policy). This was part of an explicitly stated and successful plan to erase all aspects of Indigenous cultural identities.

That’s the textbook definition of cultural genocide. And yes, formal physical violence nominally ended decades ago, but the goal to erase indigenous people as distinct from the colonizers stands.

Receipts

Sick of tables you say? Well you don’t even need to read this next one to see that there is a distinct difference between the features of Settler Colonial Englishes and Postcolonial Englishes. This isn’t a spectrum of differences, it is a binary.

It is important that we acknowledge that many of the perspectives used in academics are not just dated, but also dangerous. Failing to identify continued colonialism is a violent erasure of the indigenous cultures that were systematically dismantled under imperialist policies. And from a linguistics perspective, we can’t begin to describe World Englishes if we don’t face the cultural eradication that led to their developments. That begins with accurately identifying Settler Colonial Englishes.

Yalitza Aparicio from the hit film “Roma” shrugs and smiles adorably.

Written from the unceded Piscataway and Pamunkey land (home of the Conoy language and the extinct dialect of Nanticoke or the Eastern Algonquian family of languages).

Denis, et al. “Settler Colonial Englishes Are Distinct from Postcolonial Englishes.” American Speech, Duke University Press, 1 Feb. 2018, read.dukeupress.edu/american-speech/article-abstract/93/1/3/134811/Settler-Colonial-Englishes-Are-Distinct-from.

Schneider, Edgar W. “ Postcolonial English: Varieties around the World.” Cambridge University Press. 2007

Wolfe, Patrick. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research, vol. 8, no. 4, 2006, pp. 387–409., www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14623520601056240.