Language ideology change over time: lessons for language policy in the U.S. state of Arizona and beyond

Those silly Brexiting kweens across the pond are making headlines (por ejemplo) about implementing an English language requirement deadline for UK residents. While we wait for that sitch to shake out, it seems like a good time to dive into a bit of language policy research.

Shannon Fitzsimmons-Doolan’s (2018) paper examines the interplay between stakeholders’ language ideology and language policy in Arizona’s K-12 public schools. The related literature shows a chicken and egg situation in which language ideology drives language policy, but language policy affects language ideology. Arizona offers an interesting case study for unpacking this relationship.

Vamos a establecer la escena/Let’s set the scene

For those unfamiliar with the U.S. educational context, primary and secondary education policy is driven at the state rather than national level. In 2006 Arizona adopted the anti-bilingual/multilingual education policy Structured English Immersion, aka the 4 Hour Model, aka the No-Me-Gusta-People-That-Talk-Different model. English language learners (ELLs) are segregated into English language development classes for 4 hours a day until they reach proficiency on a state assessment. During this time these students are being withheld from content classes (math, science, etc.). These requirements can be particularly burdensome to older ELLs who are unable to get credits that would allow them to graduate from high school.

This policy was an outgrowth of the political climate in Arizona that had passed Proposition 203, a voter referendum that repealed bilingual education laws in 2000. While I would love to spend more time wagging my finger about English only policies, that’s not really why we are here.

El papel/The paper

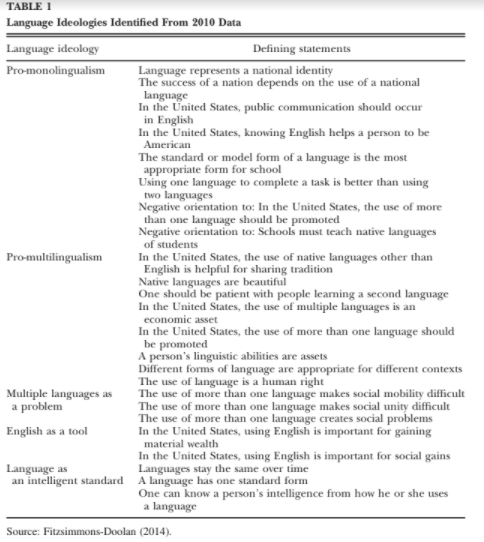

Fitzsimmons-Doolan is interested in the change in language ideology of policy-influential people in Arizona from 2010 and 2016. She surveyed politically active Republicans and Democrats, teachers in districts with high ELL populations, and education administrators who manage language policy. From the 2010 survey data she identified 5 broad language ideologies: 1) pro-monolingualism, 2) pro-multilingualism, 3) English as a tool, 4) multiple languages as a problem, and 5) language as an intelligent standard. Check out the deetz in the table below (p.40). The 2016 survey measured shifts in orientation to the ideologies above by reaching out to the same group of respondents from 2010.

Los resultados/The results

Language ideology on the survey remained pretty stable over 6 years. There were statistically significant shifts away from pro-monolingualism and multiple languages as a problem, and higher positive orientation toward pro-multilingualism. However, those shifts were concentrated in the educator respondents, and not in the politically active Republicans and Democrats respondents, who exhibited little change.

you, a linguabish: why does it matter what some some random voters have to say about language policy, the teachers and administrators implement language policy

me, someone that googled a bit: recall that Arizona has ballot initiatives, including the aforementioned Prop 203, which voters passed to severely restrict bilingual education. democracy lol

It is unsurprising that the politically active Republicans and Democrats did not change their minds greatly over time. Fitzsimmons-Doolan notes that the average age of respondents in the 2016 survey was 62.3 years old, which makes sense when you consider how much more likely older generations are to consistently go out and vote. I think opinions about language are pretty baked-in for the layperson at that age. That said…maybe no news is good news?

Given the political climate of 2016 and Drumpf’s nativist rhetoric propelling him to the Republican nomination and presidency, perhaps we can be thankful the politically-active people of a fairly red state like Arizona didn’t swing *more* toward pro-monolinguism, multiple languages as a problem, and language as an intelligent standard.

Conclusión/Conclusion

While Arizona might not be ripe for reform just yet, this research shows some positive trends away from English only policies among those who work directly with language learners. Educational language policy in AZ might continue to be a hot mess for now, but don’t lose heart, linguabishes. I believe language ideology is correlated with immigration policy preferences, and the increased polarization is going both ways. As nativists and restrictionists get more vocal, they are spawning fiercer, more outspoken allies of immigrant communities. Maybe by proxy support for bilingualism and multilingualism will intensify. (Fingers crossed.)

Check this paper out if you’re a bish interested in language policy, a bilingual educator bish, or any old, K-12 teacher bish that works with ELLs.

Fitzsimmons-Doolan, S. (2018). Language ideology change over time: lessons for language policy in the U.S. state of Arizona and beyond. TESOL Quarterly. 52 (1). 34-61.