Emoji Grammar as Beat Gestures

If you’re a Lingua Bish, you probably know about celebrity linguists Dr. Gretchen McCulloch😻 and Dr. Lauren Gawne 😻. In their presentation at the 1st International Workshop on Emoji Understanding and Applications in Social Media in June (2018), they presented their research to answer the question once and for all, Are emojis a language 🤔? But actually, Gretchen and Lauren always use emoji as the plural for emojis, (bishes don’t) and their research question was “If languages have grammar and emoji are supposedly a language, then what is their grammar?”

If you try to compare emojis to language, the closest you’ll get is word units. Of all the bits of a language, emojis are most similar to words, but language is so much more than a bunch of words. It has parts of speech and structure (and so many other things). Emojis often affect the tone of text or add a layer of emotion😏, but Lauren and Gretchen think that’s just a small part of it because their effect isn’t always straightforward. To compare emojis to words, they decided to look at the most used word sequences and compare them to the most used emoji sequences. They hypothesized that if emoji sequences are repeated they should be considered “beat” gestures, but what is that even?

Beat Gestures and Emojis

So gestures are a different type of communication🖐. They are not a language and they don’t have grammar.

One type of gesture is the “beat” gesture. It is characterized by its absence of meaning and its repetitive nature. You use beat gestures when you talk with your hands👐 and most gestures politicians make during speeches are beat gestures.

However, when a really cool person bobs their open palms up and down in the air above their head, you know it means “raise the roof”, so this is not a beat gesture. It seems like emojis act the same way as beat gestures, often repetitive and often with no inherent meaning unless accompanied by words🤯.

The Emoji Corpus

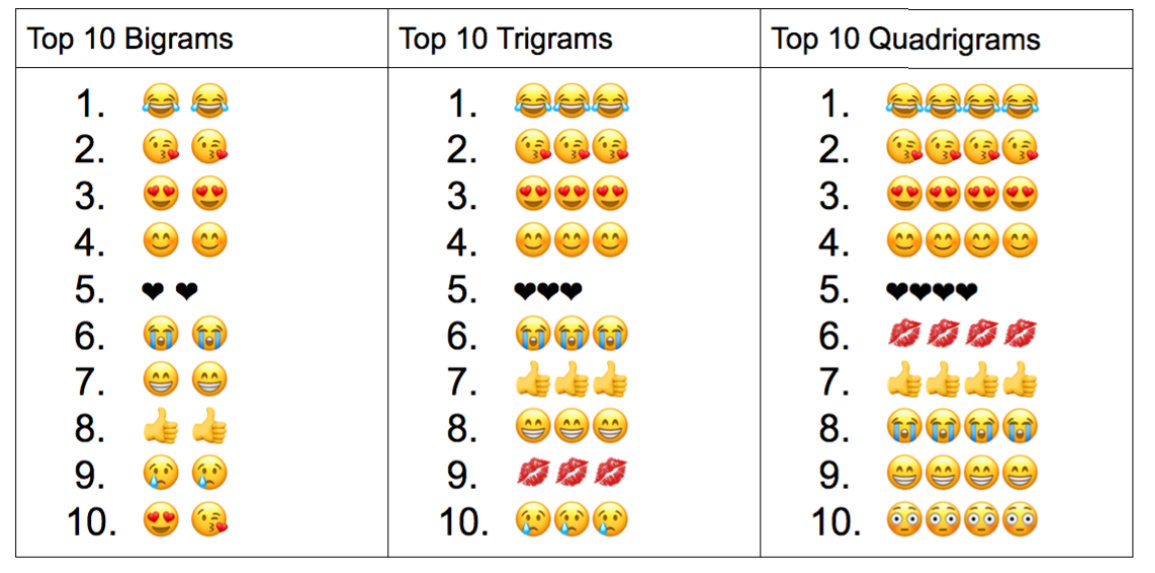

Gretchen and Lauren used a SwiftKey emoji corpus to check out sequences of two, three, and four emojis. That means that they looked for groups of emojis that often appear together. They looked for the 200 most common sequences and noticed that the top sequences used just one repeated emoji. These were the top 10 sequences in the SwiftKey emoji corpus:

The Word Corpus

Then they used the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) to check out word sequences to compare to the emoji sequences. The COCA contains around 500 million words from things like news outlets and websites👩💻. In the 200 most common word sequences, they found almost no repetition. The only time words were repeated, were in the cases of “had had” and “very very very.” However, these didn’t even make the top 200. And yes, that could just be because the COCA is formal and perhaps a corpus of informal language would have yielded different results. For example you might get instances of what linguists call the ‘salad-salad reduplication’ (2004) as in “it’s salad salad🥗, not ham salad or jello salad”. It’s the same as “OMG you like like them 😲??” or “It’s Saturday. Tonight I’m going out out💃,” but this bish is digressing.

Comparing Words to Emojis

The point is, where words are very rarely repeated in a sequence, it appears that emojis are. You’re probably like, “but I send 2-4 emojis at a time and they don’t repeat.” Ya, you might, but I bet they’re pretty similar like 5 different hearts💝💘💖💗💓, or the hear-no-evil monkeys🙈🙉🙊, or allll the dranks🍾🍹🍸🥃🍷🥂🍺. So ya, sometimes they’re all different, but if so, they’re likely on a theme.

But even though emojis can be more repetitive than speech or writing, most emojis occur next to words and not in sequences. Even where emojis occur without words, it’s mostly just one or two at a time and usually in response to a previous message. Guess who else usually partners with words? You guessed it, beat gestures👊!

It seems like emojis and beat gestures have a lot in common. Let’s list the ways:

- no grammatical structure

- no inherent meaning unless accompanied by words

- often repeated

- often add emphasis

Maybe emojis and beat gestures should get a room already 👉👌😜.

Conclusion

Basically the idea is just to shift the way we think of emojis. Thinking of them as a new language with grammar won’t get research far. Gretchen and Lauren might be on to something by considering emojis to be a type of gesture. Emojis don’t have their own grammar, but they work with our written grammar. They add emphasis, just like beat gestures do with our spoken grammar. So, it’s unlikely that emojis can ever be a full language. If they ever start exhibiting structural regularities in corpus studies though, and start languagifying, I’m sure Gretchen and Lauren will be there to catch it.

This paper is great for emoji bishes👯, anyone who texts📱, corpus bishes, and lingthusiasts👸🏻👸🏿👸🏼👸🏾.

——————————————————————————————————–

In: S. Wijeratne, E. Kiciman, H. Saggion, A. Sheth (eds.): Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Emoji Understanding and Applications in Social Media (Emoji2018), Stanford, CA, USA, 25-JUN-2018, published at https://ceur-ws.org

Ghomeshi, Jila, et al. “Contrastive Focus Reduplication in English (The Salad-Salad Paper).” Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, vol. 22, no. 2, 2004, pp. 307–357., doi:10.1023/b:nala.0000015789.98638.f9.