(This is part of a series. Check out the first post on lexical diversity here and the second post on vowel quality here.)

A commonly cited reason for why so-called ‘native speaker’ English teachers are superior to ‘non-native’ English speaker teachers is pronunciation. “How can the students learn proper pronunciation from someone with a foreign accent?” howl the haters. “Native speaker teachers speak correctly, so students will have an accurate model,” wail the whiners.

“What if accent is all in your mind?” says me.

JK JK, accents are real and we all have them. However, our perception of accents is driven by more than just the technical difference in sounds. Dr. Sara Incera and her team show that foreign accents can be wrongly accused as the culprit of communication difficulties. While most research has looked at how accent affects comprehension, this paper (2017) considers the reverse: how does comprehension affect accent perception?

They do this by looking at the effects of sentence predictability on how strongly an accent is perceived. For example, “Every morning I drink _____.” There are many things that could fit in that blank, and what your mind is expecting to hear populates as you’re processing the sentence in real time. Incera et. al hypothesize that if the sentence completion is something unpredictable like, say, “Every morning I drink… lamp”, then you will perceive a stronger foreign accent on the part of the speaker than if the completion was predictable.

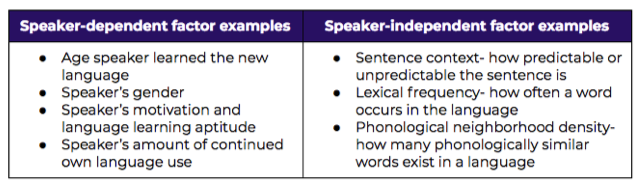

What makes this study a special, precious, unique snowflake amidst previous work on accent perception is that it isolates the speaker-independent variable of sentence predictability from speaker-dependent factors. Umm… wut. Here is a nifty table to tablesplain:

These researchers conduct two highly-controlled experiments to determine the specific effect of sentence context on foreign accent perception.

Methodology

Here is the recipe for the first experiment:

Step 1: Identify 24 freerange, artisanal sentences from Bloom and Fischer’s 1980 sentence corpus that have a highly predictable final word.These are the predictable sentences aka the snoozefest sentences.

Step 2: Chop off the final word of each sentence and swap it with another sentence. These are the unpredictable sentences aka the acid trips sentences. For example:

- After dinner they washed the _ dishes (closet)

- He hung her coat in the _ closet (dishes)

Step 3: Isolate the final word of the sentence by recording the sentence stem and final word with different speakers. Record the sentence stems in a ladyvoice by a speaker of American English. Record the final words in a manlyman voice by 6 speakers of English as a foreign language (2 Chinese speakers, 2 Hindi speakers, and 2 Arabic speakers). The gender difference is to make the final word clearly distinct so it alone will be rated for accent, but you could easily reverse the genders. Splice the recordings together.

Step 4: Find 24 randos to be your participants. They are speakers of American English. Give them some course credit for their time, please and thank you.

Step 5: Have participants each listen to a mix of 12 predictable and 12 unpredictable sentences counterbalanced from all 6 of the foreign speakers. They click on a button on the computer screen that says “Weak Accent” or “Strong Accent.” Instruct them to rate only the final word spoken by the male speaker.

Voila! You have a pile of data to eat for dinner! Bon appetit!

For the second experiment they did basically the same things, but recorded the final word with just two dudes. One dude is an American English speaker referred to in the paper as “native speaker,” and other buddy is a Hindi speaker called “foreign speaker.” This follow up experiment was to determine if the results from the first experiment extend to American English speakers.

Results

Drum roll please…In the first experiment participants were more likely to rate the speaker of an unpredictable sentence as having a strong accent. Though the exact same recording of the word in a predictable sentence was more likely to be rated as spoken with a weak accent. In the second experiment, they found that the unpredictable sentences for the “native speaker” were also rated as having a strong accent. Let us jump to conclusions:

Linguistic context affects perception of accent! This study squares with my personal experience as an ESL teacher. On the occasions that I have difficulty understanding what my students are trying to communicate it is frequently because I don’t know what they are talking about rather than their pronunciation. I might not have the requisite background knowledge to understand, or the unpredictability (and magnificent creativity!) of their word choice as English language learners throws me off the trail. As a ‘native’ English speaker and an ESL teacher, I must unlearn that my accent is superior and that communication breakdowns are the result of others’ accents.

Flipping out about a foreign accent on an English teacher is not a good look FULL STOP. 1) English as an international language or English as a Lingua Franca make this moot as most English speakers globally speak it as a second language to others who speak it as a second language. 2) Accent discrimination is a thin veil for racism, sexim, classism, jingoism, and other bad-isms. 3) As this study shows, foreign accent perception is a lot more subjective than people realize. Some of it is in our heads.

Check out this paper if you are an accent perception bish or an anti-nativespeakerism babe!

Bloom, P. A., & Fischler, I. (1980). Completion norms for 329 sentence contexts. Memory and Cognition, 8, 631–642.

Incera, S., McLennan, C.T., Shah, A. P., & Wetzel, M.T. (2017). Sentence completion influences the subjective perception of foreign accents. Acta Psychologia, 172, 71-76.