My favorite publication is American Speech, a quarterly journal published by Duke University Press. Yes, it’s a little Anglo-centric, but it has my favorite recurring feature Among the New Words. I developed a very close relationship to this feature through my master’s thesis when I used it to comb through and analyze 10 years’ worth of “new words”. That’s around 2500 words and it was an arduous, tedious, fantastic dictionary wonderland that was totally the best and the worst.

Among the New Words, hereafter to be referred to as ATNW, has the lofty mission of documenting new words and uses of words in real time. It is a totally non-traditional style of lexicography. It’s been running regularly since 1941 but had different incarnations as early as 1937. In its nearly 80 years, ATNW has gone from reader-submissions to the internet age. Ben Zimmer and Charles E. Carson decided to look at ATNWs history and consider its future in the most exciting paper I’ve read all year: Prospects and Challenges of Short-Term Historical Lexicography (2018).

How it all started

In 1933 an English teacher slash Jewish immigrant (slash, from his awesome name, I can only assume refugee from Mordor), Isidor Colodny, started publishing a monthly magazine called Words: A periodical devoted to the study of the origin, history, and etymology of English words. I guess this is the kind of thing people did before Instagram. A couple years later, Isidor (Lord of the 8th ring probably) enlisted Dwight Bolinger, a Spanish Teacher with a Ph.D. to write a column called “The Living Language”.

Bolinger noted a very important part of word collection in his introduction to the very first column. He pointed out that new words are often

“…transitory, so that they leave no mark upon the dictionary; and even those which are fortunate enough to make their way into that solemn repository are usually not recorded in such a way as to show just how they came into being, what was their original context, what suggestive power they may have had aside from their literal meaning…”

Which was basically the premise of my whole thesis btdubs. Also, “that solemn repository” is totally what I’m calling dictionaries from now on.

So Bolinger’s original method for The Living Language was to have readers submit new words and words they found to be used in new ways. They were also asked to include information about coinages (unrealistic goals much?). Even with modern resources, we can’t usually accomplish that. Zimmer and Carson use Bolinger’s entry for “hootenanny” as an example of the difficulties of dating coinages pre-internet. Bolinger dated its first use as 1935, but internet tells us it was used as early as 1906.

Nevertheless, his column reached a broad audience including co-founder of American Speech, H. L. Mencken. He was invited to join and renamed his column Among the New Words in 1941. A man before his time, he eschewed traditional domestic American life for an international, 3D immersive, freelance experience teaching in Costa Rica and performing his American Speech duties remotely.

Bolinger’s neologism spotting skills were on point. He wrote about -worthy from jump. He noticed that we had gone from seaworthy and trustworthy to all kinds of new worthies like newsworthy, courtworthy, and credit worthy par example. That was 1941. Now we have such beauties as Oscar-worthy, cringe-worthy, and meme-worthy.

Another thing he got right was that we create new words by pronouncing onomatopoeia aswords. He noted ahem and tisk. And that’s totally carried on. Just think of nom nom.

How it all changed

Bolinger passed the torch in 1944 and ATNW met a series of new editors. For the publication’s 50th anniversary, Adele Algeo and her husband John (who were running ATNW at the time) produced a commemorative edition with an overview of the different processes of documenting new words that had been used. Inspired by this, its editors (also Zimmer and Carson + Solomon) did another retrospective for its 75th anniversary.

A lot of methods were used over the years. There was a lot of reading, and submissions by readers in the beginning. In 1997 Wayne Glowka chose the “ask the kids” method by roping in his undergrad students for credit. Also, in the 90s there was this amazing new method created. It was called “electronic database searching.” So, I don’t know… Encarta perhaps? And since 2009, or “The Year of the Tweet” as I call it, access to language changed. The inundation of language from all social media platforms has made tracking neologisms less a matter of collection and more matter of curation (Zimmer and Carson 2018).

Another cool update is that the publication went digital in 2010. So now when describing a new word, writers can include links to digital media like TV, speeches, music videos, and memes.

The challenges

More access to IRL language use is awesome, but it’s also mo’ words mo’ problems. Ya gotta have a system for using search engines and determining what’s real and what’s just a google algorithm. So, let’s talk about ratchet, shall we? It was the American Dialect Society’s word of the year in 2012. ATNW’s initial treatment of it included these four senses:

- (insult) adj Over the top, to the extreme, beyond socially acceptable -1999

- (insult) n Woman who is ratchet (as in sense 1) -1999

- (neutra or positive) n Type of dance in Shreveport, La., or subgroup of rap music associated with the dance -2004

- (positive) adj Excellent, wildly fun, exceeding expectations-2007

According to ATNW’s initial entry it all basically started with one kickass grandmother in Shreveport Louisiana. That’s right, innovative wordsmith Anthony Mandigo allegedly used a word he’d learned from his granny as the title of his hot new track to usher in a new style of rap, Ratchet Rap. ATNW speculated that the word could have come from “wretched.”

But wait! After the publishing, a reader found an earlier use of the word (that’s called antedating btw). It was used in its first sense in 1992 song “I’m So Bad” by UGK, a delightful ditty about S-ing one’s own D as far as I can tell. UGK was from Texas. To this day, that’s all ATNW knows.

All of this illustrates that you can’t just do a google search and call it a dictionary. If the ATNW editors were listeners of rap from 1992 Texas, they would have been able to write a much more informed entry. Clearly, people have been using ratchet since before 1992- UGK didn’t make it up. It also is a lesson on diversity and inclusion because, stop me if I’m wrong, but I have an image in my head of what the editors of ATNW and those solemn repositories have traditionally looked like, what kind of music they’ve listened to, and which regional dialects they’ve used and I’m willing to bet “ratchet” wasn’t in their lexicons.

So, when you conduct your search of “electronic databases” and the like, you need to thoroughly investigate the source (time and place) and look for whoever was producing content at that time. Rarely are words coined out of the blue, so even if you can’t find any more instances of the word, then call a friend. Someone you know knows someone who knows someone from that area. Sherlock the heck out of that shit!

This article is great for historical linguistics bishes, lexicography bishes, and Ben Zimmer stans.

—————————————————————————————————————————

Zimmer, Benjamin, and Charles E. Carson. “‘Among the New Words’: The Prospects and Challenges of Short-Term Historical Lexicography.” Dictionaries: Journal of the Dictionary Society of North America, vol. 39, no. 1, 2018, pp. 59–74., doi:10.1353/dic.2018.0010.

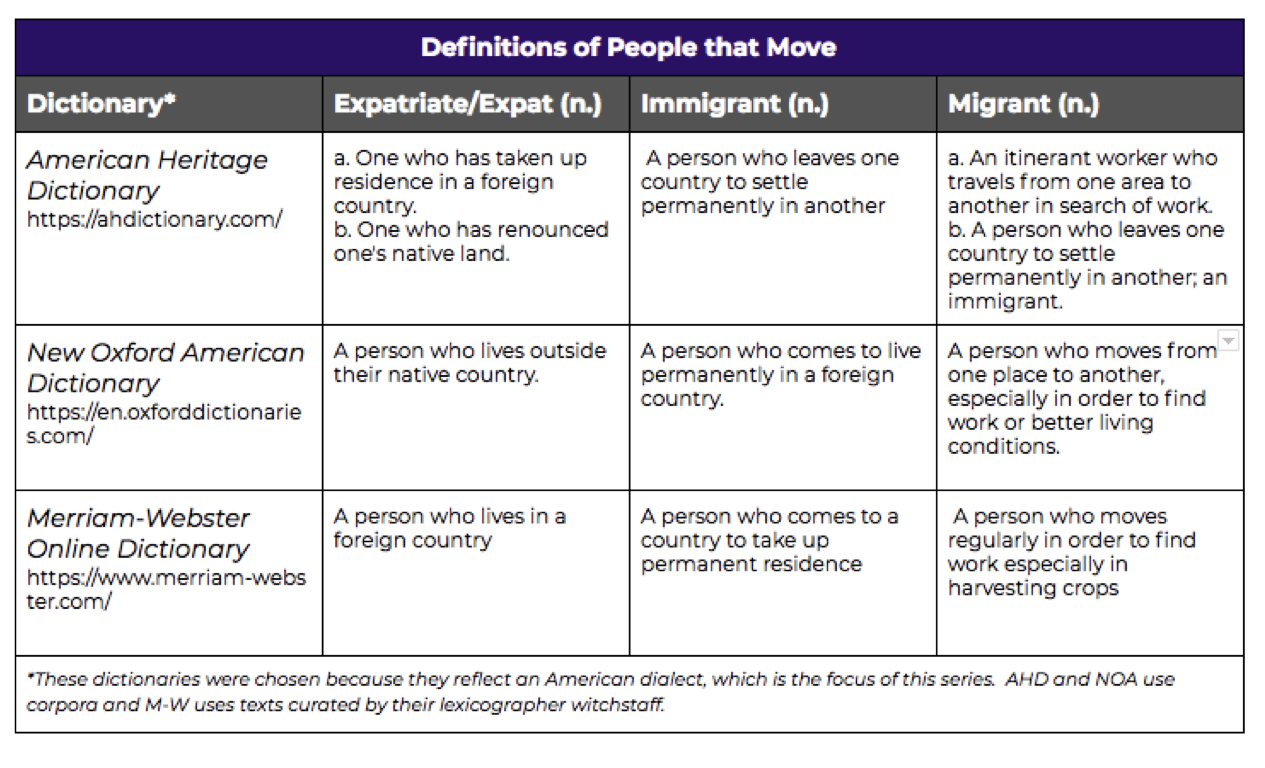

As you can see with your own beautiful eyes, the distinctions are subtle. (Also, how extra is

As you can see with your own beautiful eyes, the distinctions are subtle. (Also, how extra is