Happy Birthday to us! We’ve been doing the bish thing for a year, so I guess we have to do that tired old practice of recapping because like Kylie, we had a big year.

TL;DR – following is a list of our plans for 2019 and a recap of what we learned in 2018.

#goals

-

- We’re looking for guest writers. So if you know any other linguabishes, send them our way.

- We’re diversifying our content to include not just peer-reviewed articles in academic papers, but also conference papers, master’s theses, and whatever else strikes our fancies.

- We’re planning to provide more of our own ideas like in the Immigrant v. Migrant v. Expat series (posts 1, 2, and 3) and to synthesize multiple papers into little truth nuggets.

- Hopefully it won’t come up, but we’re not beyond dragging any other racist garbage parading as linguistics again.

Plans aside, here’s all the stuff we learned. We covered a lot of topics in 2018, so it’s broken down by theme.

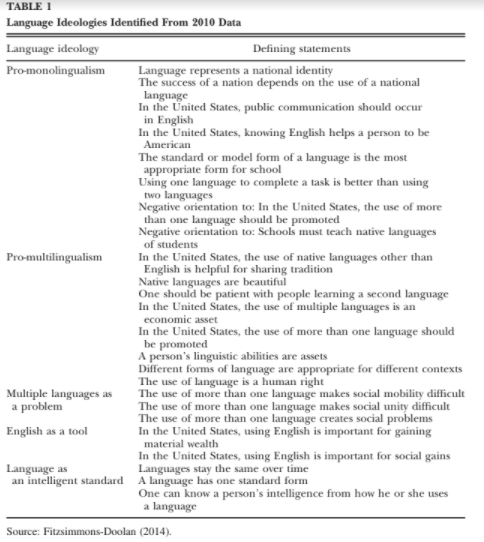

Raciolinguistics and Language Ideology

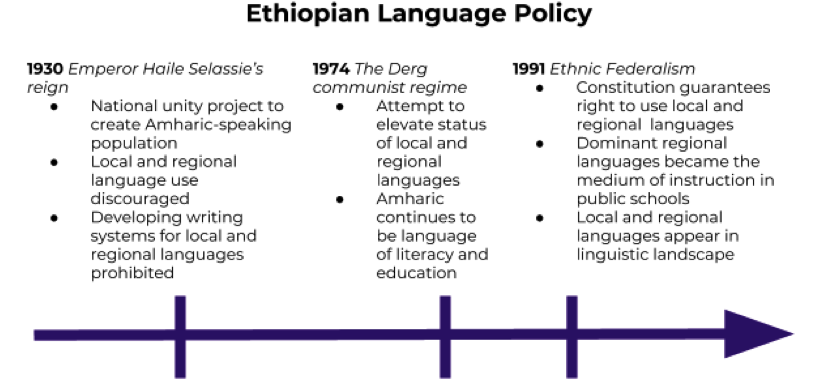

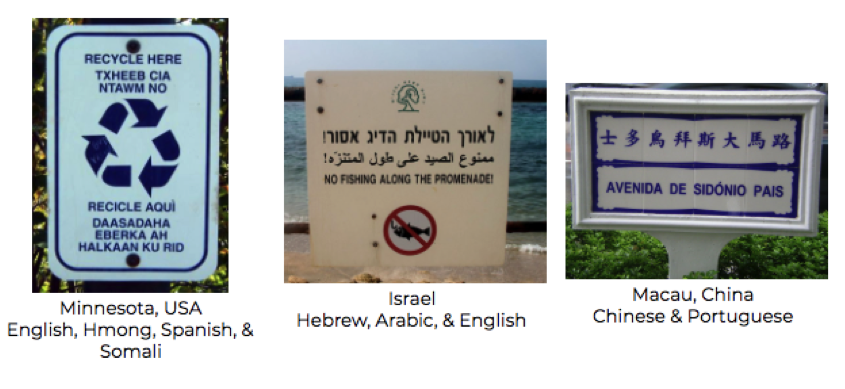

We wrote 5 posts on language ideology and raciolinguistics and we gave you a new word: The Native-speakarchy. Like the Patriarchy, the Native-speakarchy must be dismantled. Hence Dismantling the Native-Speakarchy Posts 1, 2, and 3. Since we had a bish move to Ethiopia, we learned a little about linguistic landscape and language contact in two of its regional capitals. Finally, two posts about language ideology in the US touch on linguistic discrimination. One was about the way people feel about Spanish in Arizona and the other was about Spanish-English bilingualism in the American job market.

Pop Culture and Emoji

But we also had some fun. Four of our posts were about pop culture. We learned more about cultural appropriation and performance from a paper about Iggy Azalea, and one about grime music. We also learned that J.K. Rowling’s portrayal of Hermione wasn’t as feminist as fans had long hoped. Finally, a paper about reading among drag queens taught that there’s more to drag queen sass than just sick burns.

Emojis aren’t a language, but they are predictable. The number one thing this bish learned about emojis though is that the methodology used to analyze their use is super confusing.

Lexicography and Corpus

We love a dictionary and we’ve got receipts. Not only did we write a whole 3-post series comparing the usages of Expat v. Immigrant v. Migrant in three different posts (1, 2, and 3), but we also learned what’s up with short-term lexicography, and made a little dictionary words for gay men in 1800’s.

Sundries

These comprise a grab bag of posts that couldn’t be jammed into one of our main categories. These are lone wolf posts that you only bring home to your parents to show them you don’t care what they think. These black sheep of the bish family wear their leather jackets in the summer and their sunglasses at night.

Dank Memes

Finally, we learned that we make the dankest linguistics memes. I leave you with these.

Thanks for reading and stay tuned for more in 2019!

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linguistic_landscape

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linguistic_landscape