The United Nations declared 2019 the International Year of Indigenous Languages. This post is part of a series covering research in the area of indigenous languages.

Before English, French, and Spanish more or less prevailed in North America, the OG residents of this continent engaged the invading languages and their speakers in a variety of ways. The linguistically diverse Native populations of North America were influencing and being influenced in language encounters with the Eurotrash groups that were settler-colonizing their land in the 16th-18th centuries.

Sean P. Harvey and Sarah Rivett’s essay (2017) covers a lot of ground: language change, language policy, pidginization and creolization, linguistic imperialism, interpretation and translation, language acquisition, language death. All the most fascinating –isms and –ations. Dear broken-brained internet reader, here is snackable list of some such colonial-indigenous language encounters.

Full paper recommended for indigenous language lovers and historical linguistic hoes.

- Literacies

There’s an old narrative that Native peoples had oral cultures and Europeans bestowed literacy upon them. But understanding has started to shift: indigenous peoples had graphic systems long before the whites came along and proceeded to not recognize such systems as literacy (p.457). There were syllabic glyphs and pictographic codices in MesoAmerica. North of Mesoamerica petroglyphs, birch bark scrolls, buffalo hides painted, wampum (beading) were used for recording events and communicating. Many of these graphic forms coexisted with and integrated European literacy. A European traveler wrote that he was told by an Ojibwe person that “his people used the same word, masinaigan, to refer to both birch bark scrolls and to white people’s books (p.471).”

- Orthography Development

Some Native people were inspired by European literacy to develop writing systems for their own languages (p.443). Sequoyah of the Cherokee nation created a syllabary, a set of written symbols that represent syllables, for his language. It was adopted by the Cherokee people and (euro-style) literacy skyrocketed. Some of the characters in the syllabary resemble letters from the Roman alphabet, but have no connection to the sounds used in European languages. The white people found this irritating because they wanted a standardized alphabet to make things easier for themselves, but Sequoyah was like #sorrynotsorry.

- Pidgins, Creoles, and Mixed Languages

In some communities indigenous languages and colonial languages mixed, often through intermarriage and the children of these unions. The Metis people in the Red River region- current Minnesota and North Dakota, USA/Manitoba, Canada- came to speak Michif, a mixed language (p.451). Michif features verbs in Cree, an Algonquian dialect, and nouns in French… a Latin dialect (lol I went there).

- Lingua Franca

Lingua francas emerged to mediate communication between indigenous and colonial people. Late into colonization of the Americas indigenous languages were still used as lingua francas in areas with fewer settlers than Natives. For example, in the mid-17th century, settlers used Pequot, an Algonquian language, to communicate with the Wampanoag, Narragansetts, and Mohegans in southern New England (p.452).

- Language Learning & Teaching

Sometimes framed as “assistants” to missionaries and traders, scholars now recognize indigenous individuals’ agency to act or not act as language teachers to colonists and settlers. For some indigenous people language teaching could be an act of gaining influence and for others it was an act of #resistance. Harvey and Rivett point out that Euro-americans learning local languages was entirely dependent on Native participation. While some Native people chose to teach their languages to new arrivals, many others refused or sabotaged language learning efforts by giving wrong information or mocking the would-be students (p.454). Just imagine all the colonist hipsters walking around with bad tattoos in indigenous languages.

- Classification

Colonists could not wrap their heads around the linguistic diversity of the Americas. There are accounts of them attempting to trace languages in the Western Hemisphere to Hebrew, Phoenician, Chinese, Welsh, and Dothraki probably. They also tried to classify languages by similarity and identify which indigenous languages were derived from others. Their motivations were to determine alliances and clearly delineate “nations” and “tribes” that could cede land. These efforts also coincided with emerging ideas about race. Wampanoags and Powhatans were lumped together as a “race” as a result of linguistic “analysis.” WUT. Native peoples were not trying to help the colonial types draw lines around them or make their languages manageable to the administrative arms of imperial powers. Harvey and Rivett note that Native people had completely different conceptions of linguistic relationships than the Europeans, which stymied classification attempts (p.463). I think that calls for another #sorrynotsorry

There were many more encounters that we weren’t able to fit here in bishland, but check out the full paper!

______________________________________________________________________________

Harvey, S. P. & Rivett, S. (2017). Colonial-indigenous language encounters in North America and the intellectual history of the Atlantic world. Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 15 (3). 442-473. 10.1353/eam.2017.0017.

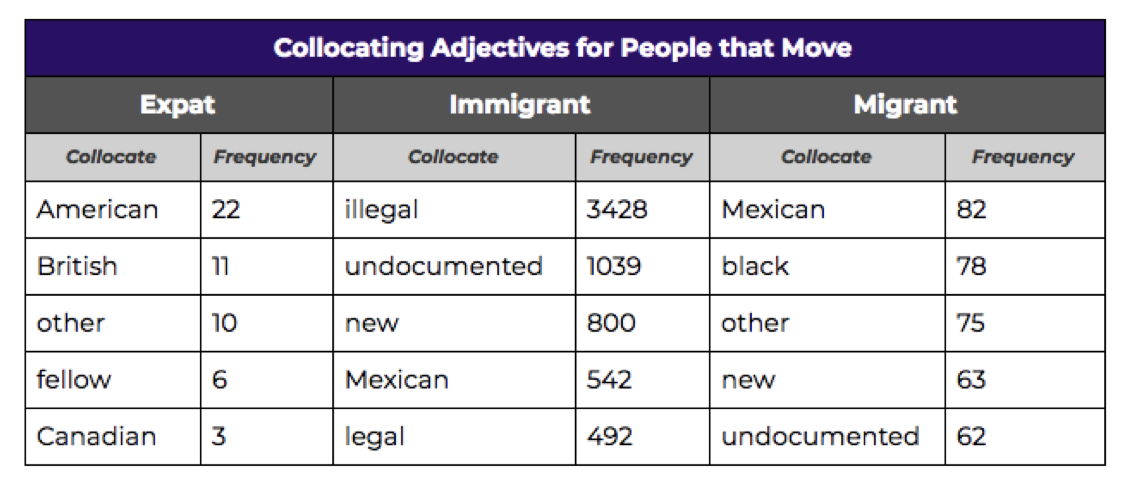

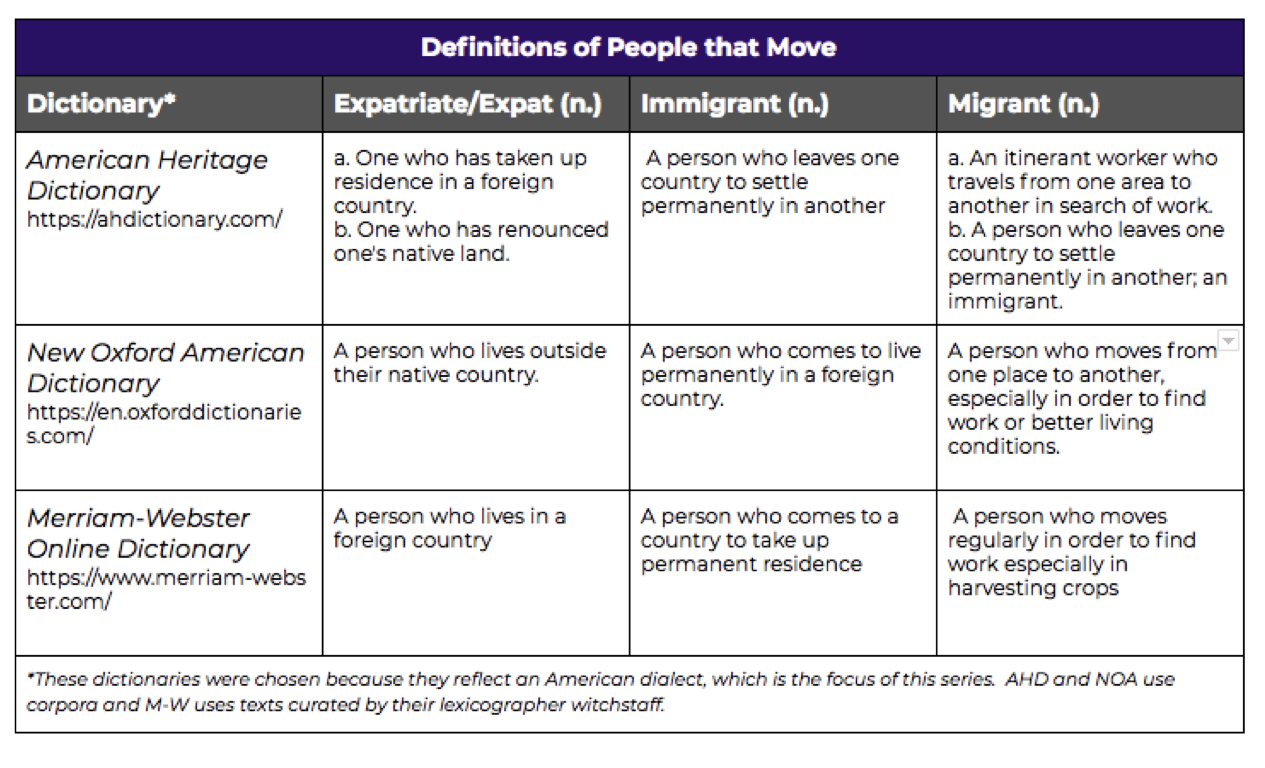

So what are we looking at here in this table? For each of the People that Move lexical items you can see the top five adjective collocations that go before them. Meaning when I searched for

So what are we looking at here in this table? For each of the People that Move lexical items you can see the top five adjective collocations that go before them. Meaning when I searched for

As you can see with your own beautiful eyes, the distinctions are subtle. (Also, how extra is

As you can see with your own beautiful eyes, the distinctions are subtle. (Also, how extra is

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linguistic_landscape

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linguistic_landscape