(This is the second post in the series “Dismantling the Native-speakerarchy.” Check out the first post here.)

It’s time to pull another Jenga block out of the Native-speakerarchy tower. That block is vowel quality in English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) interactions brought to you by the Asian Corpus of English.

ELF v. EFL

English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) is often defined in juxtaposition to English as a Foreign Language (EFL). Yes, yes, the acronyms are irritatingly similar. Don’t shoot the messenger.

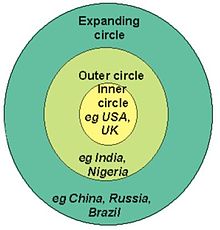

ELF refers to English used by speakers of other languages for intercultural communication. Think a French girl and Thai boy falling in love with English as their medium of communication. Or a Korean businesswoman negotiating with a Chinese board of directors in English. ELF prioritizes intelligibility and acknowledges that users will have variations (dropping articles, using relative pronouns like who and which interchangeably, etc.) that deviate from ‘native-speaker’ norms. The variations are a feature not a bug. A natural occurrence in language patterns, not a deficit.

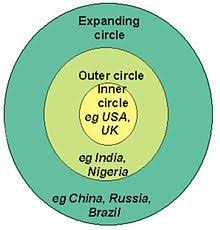

Whereas, English as a Foreign Language is designed to prepare users for communicating with a ‘native-speaker,’ and implied is an attempt to conform to inner-circle (U.S., U.K. etc.) standards. Think a Japanese student studying English to matriculate in a Canadian university. Deviations from the standard are errors. English language instruction in an EFL model seeks to raise students’ accuracy levels to be accepted in academic and professional settings dominated by ‘native-speakers.’ Individual teachers of EFL might not have that philosophy, but mass market coursebooks, curriculum, assessments, and hiring practices demonstrate the pervasive nature of the ‘native-speaker’ norms.

Back to my bae, ELF. English as a Lingua Franca is a threat to the status of ‘native-speaker’ teachers as the gatekeepers of English AND I AM HERE FOR IT. ELF speakers bring the richness of their accents to English, and they don’t have time for all of English’s quirks. Third person singular ‘s,’ I am lookin’ at you.

The Paper

David Deterding and Nur Raihan Mohamed (2016) used the Asian Corpus of English (ACE) to investigate the impact of vowel quality on intelligibility. ACE is a collection of “naturally occurring, spoken, interactive ELF in Asia.” A veritable playground for ELF fanatics.

The OG ELF fangirl Jennifer Jenkins wrote the literal book on it and identified the Lingua Franca Core: a list of pronunciation features that are necessary to comprehensibility in English. Spoiler alert: it’s a short list. It includes “all the consonants of English apart from the dental fricatives,the distinction between long and short vowels, initial and medial consonant clusters, and the placement of intonational nucleus.” (Deterding and Mohamed, 2016, p. 293).

Lemme ‘splain.

- Most consonant sounds are necessary for intelligibility. However, the pesky sounds /θ/ as in thot and /ð/ as in that hoe over there are not necessary because substitutions like /f/, /v/, /d/ typically suffice.

- Short v. long vowels. You know, your sheets v. shits, and your beachs v. bitches, etc. Mastering vowel length is considered important for intelligibility according to Jenkins’ research.

- Initial and medial consonant clusters. Sounds like /str/, /mp/, /xtr/, /pl/ /scr/, and so on at the beginning of words, and to a lesser extent, in the middle of words, need to be kept intact for the speaker to be comprehensible.

- Placement of intonational nucleus: This is stress on a syllable in an intonational unit (group of words), and the wrong stress can throw off the listener, so Jenkins includes it in the Lingua Franca Core.

All other pronunciation features are deemed fair game in ELF by Jenkins, including vowel quality, which is what this paper focuses on. Vowel quality refers to what makes vowels sound different from each other: “I must leave the pep rally early to get a pap smear. Pip pip!”

Vowel quality is why JT’s delivery in “It’s Gonna Be Me” spawned this meme:

From ACE, Deterding created the Corpus of Misunderstandings (incidentally, the name of my emo band) with data from exclusively outer and expanding circle English speakers.

This paper is building on Deterding’s earlier 2013 work that determined 86% of misunderstandings in CMACE involved pronunciation. He and Mohamed dig into vowel quality specifically because it was left off the Lingua Franca Core by Jenkins.

Of the 183 tokens of misunderstanding in the corpus, 98 involved vowel quality. In many of those tokens vowel length and quality was an issue, but as vowel length is part of the Lingua Franca Core, they were not included in the analysis, leaving 22 tokens of short vowels misheard for other short vowels. Half of these tokens included /æ/ and /ɛ/, referred to as the TRAP and DRESS vowels in the literature, but what we will call the SASS and FEMME vowels.

When they analyzed each of the 22 tokens in context, they found other pronunciation features that probably caused the misunderstanding, and that vowel quality was indeed a minor factor. For example, “In Token 5, wrapping was misunderstood as ‘weapon’, but the key factor here was the occurrence of /w/ instead of /r/ at the start of the word” (p.229). Recall that consonant sounds are in the Lingua Franca Core and play a big role in intelligibility.

Conclusion

David Deterding and Nur Raihan Mohamed’s research supports Jenkins’ contention that conforming to ‘native-speaker’ standards in vowel quality is unnecessary for English users to successfully communicate. Let me put on my extrapolation cap because you know how I do. ‘Native-speaker’ English teachers don’t have a pronunciation edge over ‘non native-speaker’ teacher colleagues when it comes to vowel quality. It literally does not matter if someone pronounces it, “Thet’s eccentism, you esshet!”

Check out this article if you are a research bish that wants to see the kind of work that can be done with corpus linguistics. And if you’re a EFL bish or an ELF kween. And if you’re a NNEST.

ACE. 2014. The Asian Corpus of English. Director: Andy Kirkpatrick; Researchers: Wang Lixun, John Patkin, Sophiann Subhan. https://corpus.ied.edu.hk/ace/ (May 26, 2018)

Deterding, D. & Mohamed, N. R. (2016). The role of vowel quality in ELF misunderstandings. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 5(3). 291-307.

Jenkins, J. (2000). The phonology of English and an international language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.