Baker and McEnery (2017) wanted to find out what the public representation of gay men was in the 1700’s. Of course they weren’t called “gay men” back then and there was a broad range of male-on-male activity that guys could engage in to be considered anything from a sinner to a sorcerer. So this is actually a look at the public representation of guys who did what Jonathan Van Ness would call “gay stuff.”

Unfortunately this study only covers gay men because of how little writing exists about other queer people from that very binary time. The approach was to explore how gay men were written about. And let’s remember that gayness wasn’t just taboo or frowned upon, it was a capital offense and was only legalized in the UK in 1967.

Source

They used the Early English Books Online Corpus version 3 (EEBO v3), which is great, but unfortunately it’s got so much religious stuff (from meeting minutes to plays and journalism) that results are a bit lopsided.

Challenges

As mentioned above, the large number of religious texts skewed the results. For example sodomite is by far the most frequent term, but it’s mostly used in a Bible-y context (you know, the whole Sodom and Gomorrah thing). The word collocates the most consistently with Genesis, filthy and some guy called Lot because the Sodom and Gomorrah story was in a bit of the Bible called Genesis and the city Sodom had the cute nickname Filthy Sodom. And also Lot was there, I guess. In the Bible-y sense, the word connoted wickedness, sin, and other deeply negative things, but not necessarily gay stuff. So none of that information is particularly relevant to the public perception of gay men in the 1700’s.

Just as an interesting side note, the word sodomite declined in usage over the century while at the same time there was a rise in church doubt and anti-catholic writings. Also, sodomite collocates with harlot and whore, the only apparent link to sex of any kind.

The other thing is that gay-stuff was just really the most marginal. There was a ton of censorship, with trial records being destroyed and there’s no evidence in the EEBO-v3 of any man self-identifying as ‘into dudes’ because they could have been imprisoned, had their wealth seized, or even been put to death. So what remains in writing is heavily prejudiced, negative, religious, based in mythology, and controlled by the homophobic patriarchy.

Finally there’s the problem of the searching part. Like, what were they to even search the corpus for? They couldn’t search any of our modern terms like homosexual, gay or queer, so then what? What they did was familiarize themselves with the corpus and use their own knowledge and words from the Lexicon of Early Modern English (LEME) and the Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary. They also found more words as they went through. Armed with all the terms for homosexuals and male prostitutes who serviced men they could find, they dove in.

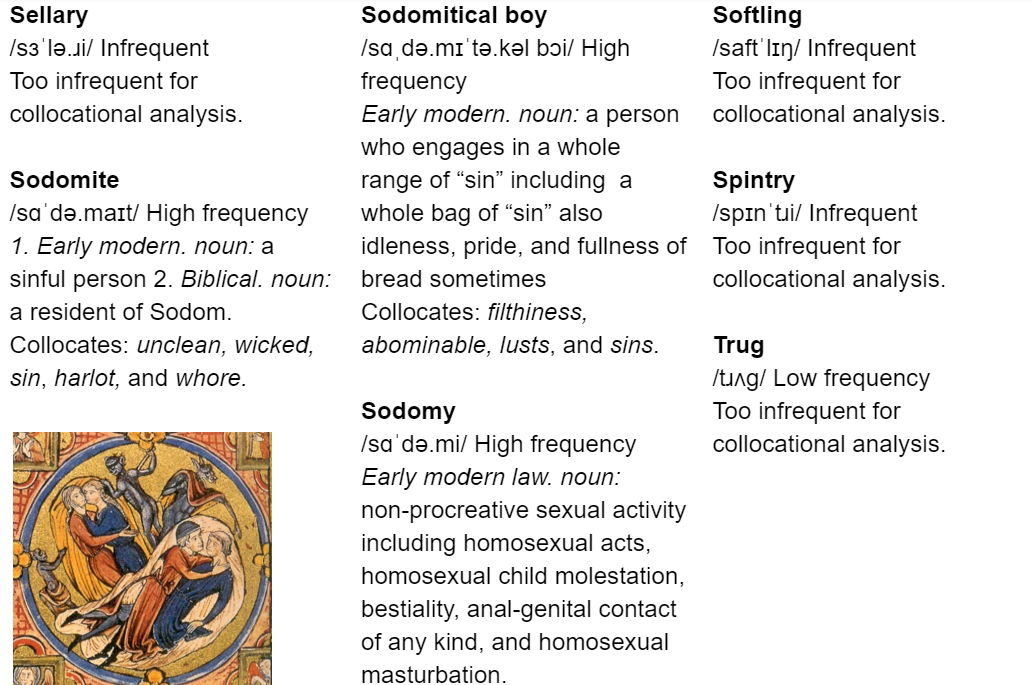

What I did

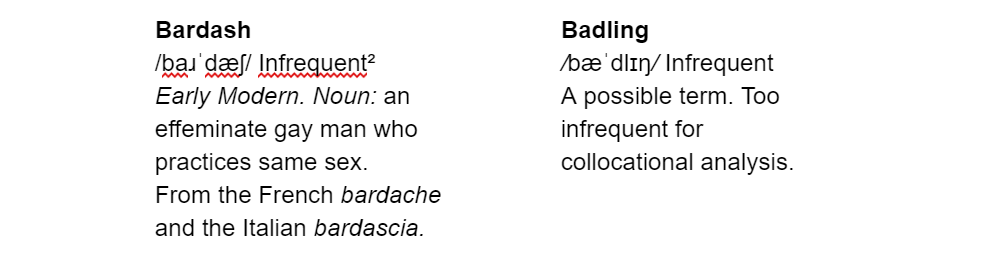

I took all the words McEnery and Baker searched for and all the words they found in EEBO-v3 and presented them in a dictionary format to accompany this post (click here for dictionary). When possible, I’ve included the metadata from the paper like frequency in the EEBO-v3, era, and definition. From my own brain parts I contributed part of speech and pronunciation. The definitions are those that Baker and McEnery arrived at through collocational analysis. Those without definitions weren’t found in the corpus or weren’t used in a way that allowed for analysis.

Example:

² High Frequency is greater than 500 hits in EEBO-v3, Mid Frequency is between 500 and 100, Low Frequency is from 10 to 100, and Infrequent is anything fewer than 10.

Side note: My intention is for this to be fun because some of the words sound ridiculous to our 21st Century ears (he-strumpet comes to mind), but I would like to acknowledge that none of these were kind-hearted terms. They represent oppression and hate written into law. These laws penalized anyone the cis-gendered heter-normative patriarchy found threatening. I went into this study with a love for lexicography, polysemy, and history, but it’s impossible to explore all of these words without experiencing a deep sadness and regret for the centuries of suffering these words represent.

Conclusion

Seems like only people who thought homosexuality was deviant wrote about it and wrote meanly so. There isn’t a single self-referential use of any of these terms in the whole corpus. However, it is definitely interesting that sexual orientation was at least referenced because there are scholars who claim that homosexuality wasn’t conceivable at that time. These words seem to argue against that.

Also cool is that there are so many different terms. Which to me says that there wasn’t just one concept of a man who was into “gay stuff,” but a variety of different ways to get involved. Sodomy could lead to execution, but ganymede and catamite weren’t accompanied by legal sentences. My favorite realization is that effeminacy wasn’t considered an indicator of sexuality. Apparently, it began to be associated with male homosexuality in the next century at which time guys who were afraid of retribution had to stop kissing each other in greetings and holding hands in public. Finally, it’s interesting that foreign languages and ancient Greek and Roman sources played a big role. And many authors described “these people” and “their acts” as being outside of England. So xenophobic.

Baker and McEnery have one final note for corpus linguists: get back to the text and get into concordancing. It’s called close reading and it involves looking beyond your five word context. Try it. I know I will be.

This article is great for lexicography bishes, history bishes, corpus bishes, and queer bishes.

Click here to proceed to the Dictionary of 17th Century Terms for Homosexual Men

————————————————————————————————————

Mcenery, Tony, and Helen Baker. “The Public Representation of Homosexual Men in Seventeenth-Century England – a Corpus Based View.” Journal of Historical Sociolinguistics, vol. 3, no. 2, Jan. 2017, doi:10.1515/jhsl-2017-1003.