It’s December and December means end of year lists. Here are some of the words that caught our eye with their ascendance in 2018 and their creative fulfillment of some essential communicative voids.

By the way, 1) this list is alphabetical because we love all our lexical babies equally, 2) we don’t get our panties in a bunch over what a word is, so the list includes phrases that operate as semantic units, and 3) this list is heavy on the internet lingo and usage because we are millenials who don’t have IRL conversations with anyone ever.

-

big mood

noun phrase: something relatable

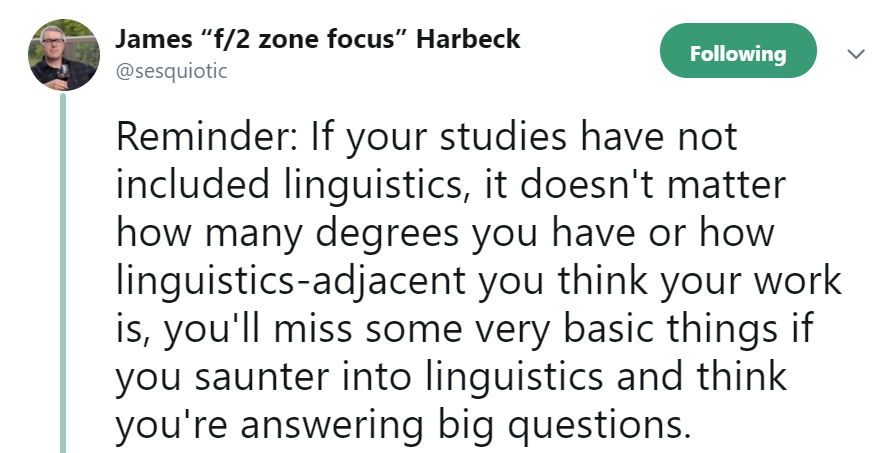

This one has been percolating for a bit. It showed up on Urban Dictionary on September 14, 2017, but it’s presence has continued to grow this past year. Says who? Says The Daily Dot, an internet publication that covers internet news. The Daily Dot credits “big mood” and its less intense cousin, “a mood” to Black Twitter and argues it’s a replacement for TFW (that feeling when) which peaked in Spring 2017. On social media a mood and big mood frequently accompany a reaction GIF or image, but it can also be a response to something relatable.

https://twitter.com/netw3rk/status/976676825832157185

https://twitter.com/Nicole_Cliffe/status/1054448958838255617

https://twitter.com/charles_kinbote/status/1075426796349374464

https://twitter.com/CatIMGs/status/1075796532098666497

-

the brands

noun phrase: multinational corporations, especially their PR and social media arms

The concept of brand has been around since 2700 BCE when the ancient Egyptians started branding livestock to differentiate their cattle from a neighbors. Then the merchants were like, “good idea,” and started using symbols and names to brand their swag. The ubiquity and importance of brand in business has led to the word’s usage for individuals: “my personal brand” and such and such behavior is “on brand.”

Over this past couple years we noticed the word being used in a slightly new way online. The brands refers to an amorphous group of multinational corporations. It’s usually derisive and often used to poke fun of corporations when they are performing wokeness or trying to be playful online.

The Brands are now trolling the President. https://t.co/V1HOPGfKqQ

— Jeff Blehar is *BOX OFFICE POISON* (@EsotericCD) January 3, 2018

Thank you to all the brands out there respecting women today https://t.co/G7k7cSH4UA

— The Outline (@outline) March 8, 2018

https://twitter.com/yusefroach/status/1046818684331646978

We regret to inform you the brands are at it again pic.twitter.com/OYk83MR6oJ

— alex (@A_Bone_Head) December 17, 2018

-

canceled

participle adjective: to reject or dismiss something or someone

The top definition of canceled on Urban Dictionary was submitted on March 10, 2018 and reflects an emerging usage among the extremely online types: such and such person or thing is canceled on account of sucking. Canceled frequently collocates with a time reference and, for some inexplicable reason, men. JK… it is extremely explicable.

https://twitter.com/lifeofnets/status/1054752083507888128

https://twitter.com/jaehwanet/status/1075326343938625536

Pigs in blankets are cancelled, this year we're eating bacon wrapped halloumi pic.twitter.com/ZAUSy02Zmf

— JP (@Jprz1321) December 19, 2018

2018 sucks. 2018 is cancelled. i'm ready for 2019 so i can become a new BITCH

— ◡̈ (@huffhuffpass_) November 20, 2018

-

thank u, next

verb phrase: expressing gratitude and readiness to move on

“thank u, next” is the “boy, bye” of 2018. Ariana Grande publicly addressed her high profile break ups when she released the track “thank u, next” telling her exes later gators, but also thnx. It’s polite and dismissive, a compliment and a sick burn. We all need this semantic unit in our lives.

If you do a search for “thank u, next” on Twitter, your results will be clogged with references to the record-breaking song. But stick with it and you’ll find people starting to use it to punctuate their posts ranging from defenses of the cast of CW’s Riverdale to feminist statements. It seems to be mostly applied as a performative utterance to indicate the speaker has finished saying what they need to say and are dismissing their interlocutor.

https://twitter.com/_scaraguilar/status/1074702612426092545

https://twitter.com/prolifegirly/status/1077188033240317952

Here’s a piece of advice. If you don’t like Riverdale, that’s fine. Just don’t attack the cast because of it. It’s not their fault, it’s literally their jobs as actors to play out the story that’s been given to them. Thank u, next.

— Adam 🏳️🌈 (Taylor’s Version) (@abnormallyadam) December 16, 2018

I just want to say.

I'm sorry for everyone I hurted this year. Thank you for all this joyful and painful rollercoaster ride. Thank you for all the memories, all of them. I cheerish all the good and bad memories and all the experience.

thank u, next.

— Svetlana Kuznetsova (@caarricd) December 23, 2018

-

Weird flex but OK

noun phrase: “I am not sure why you are bragging about that. However, it’s fine.”

Okay, this one– and, let’s be real, the whole list– is pretty memey (memish? memical?), but Oxford Dictionaries shortlisted Big Dick Energy for their WOTY, so we are going to do what we want with this list.

This phrase is a rejoinder to someone bragging or showing off about something they really shouldn’t be. Flex has been used in African American English to mean bragging, boasting, showing off, etc. for a long time, but Weird flex but OK emerged more recently. Since October 2018 there have been 7 entries in Urban Dictionary defining it in similar ways and one even bemoans it’s overuse and subsequent lack of meaning. The phrase made it on Buzzfeed’s top memes of 2018 and has been covered by multiple ‘splainers like this and this and this. It’s pretty fresh, so we shall see if it has staying power.

Weird flex but ok https://t.co/zyVQ8Oj0xo

— sarah schauer 🦂 (@sarahschauer) September 24, 2018

I’m credited with “weird flex, but ok” and to that I say

Weird flex, but ok pic.twitter.com/3MyBN1xHpg

— sarah schauer 🦂 (@sarahschauer) December 14, 2018

Saying “weird flex but ok” to a large bear as he brutally mauls me, causing immense damage to my dick and balls

— John E. Cakes (@mattytalks) December 17, 2018

Weird flex but ok. https://t.co/BAkrWnQNBn

— Ted Deutch (@RepTedDeutch) December 11, 2018

Please voice your questions and disagreements in the comments. Also, keep an eye out for words with fresh faces in 2019!

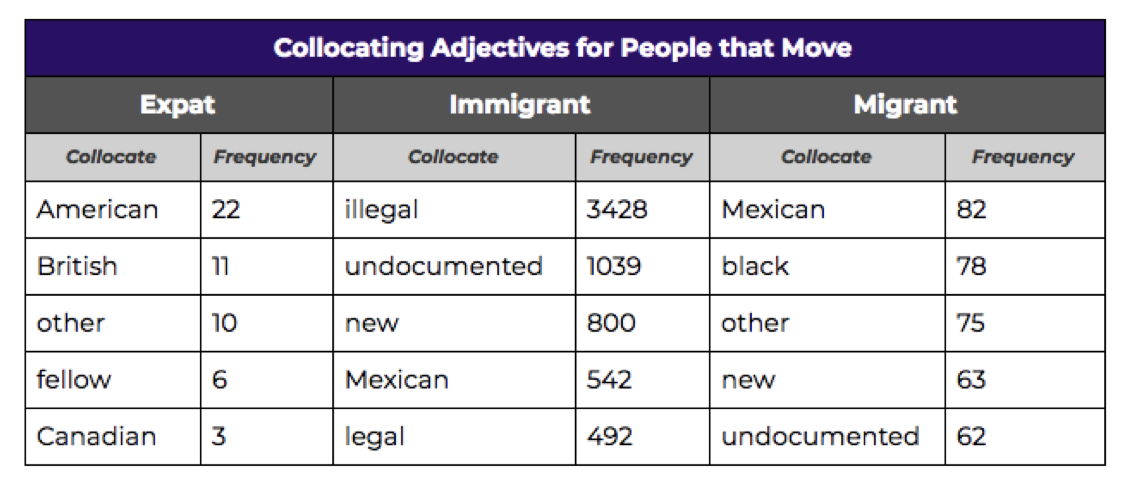

So what are we looking at here in this table? For each of the People that Move lexical items you can see the top five adjective collocations that go before them. Meaning when I searched for

So what are we looking at here in this table? For each of the People that Move lexical items you can see the top five adjective collocations that go before them. Meaning when I searched for